Ancestral Ri[gh]tes

Read More

-

![]()

Saint Martín de Porres (1579-1639)

“Forgive my error, and please instruct me, for I did not know that the precept of obedience took precedence over that of charity.”

St. de Porres was the son to Don Juan de Porras y de la Peña, a Spanish nobleman, and Ana Velázquez, an ex-slave. At an early age his father abandoned the family and left them in poverty. With little money to raise two children, his mother sent him away to apprentice as a barber-surgeon where he learned to practice medicine. He applied those skills to serving the community after he decided on a devoutly religious life.

Although St. Martín de Porres is now hailed as the saint of Mixed Race people, barbers, and public healthcare workers, during his lifetime he was not a welcome member of the Catholic church. As a descendent of a slave he was barred from becoming a member of the clergy. His only entrance was to start as a donado - a lowly servant that performed menial tasks for the church in exchange for wearing the habit and living with the religious community. But, Martín was committed to living an altruistic life committed to serving the poor and sick that even the most dogmatic of clergy had to recognize. By the end of his life he refused multiple times to be elevated to a priest, and instead chose to stay in charge of the church’s infirmary.

No one was below Father de Porres. He abstained from following draconian religious doctrine and helped those who were seen as unworthy throughout his life. However, it was not until 1962, after the Catholic church saw declining membership amongst Black parishioners, that Father de Porres was canonized.

-

![]()

Ine Kusumoto (1827-1903)

“The examination of Ine’s life story in the context of the social networks in which she participated adds to the growing body of evidence that certain women were able to participate in activities beyond the private sphere in Edo-period Japan,” Ellen Nakamura on Ine Kusumoto.

Famously known as Japan’s first female doctor and obstetrician, Ine Kusumoto was one of the first women to practice Western-style medicine during the Edo period when Japan was first introducing Western methods. Ine’s parents were Taki Kusumoto and Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold, a prominent Dutch-German physician teaching Western medical techniques in Japan. He was banished from Japan in 1829 during the Era of Isolation, where the law prohibited Japanese wives and children of foreign men from leaving. Siebold financially supported Taki and their daughter from Europe throughout their lives.

At her father’s request, Ine was educated from an early age by two of his closest students, learning medicine and the Dutch language. Apprenticing in obstetrics under one of them for several years, at eighteen, she was tragically assaulted by her trusted mentor and became pregnant. Raising a new daughter with her mother, this hardship did not put a halt to Ine’s determination to become a doctor. Refusing any contact after her assailant requested to be involved in her child’s life, Ine continued studying obstetrics with highly regarded rangaku (Dutch Learning) scholars.

New doors opened when her father was pardoned and returned to Japan in 1859, broadening her experience by gaining more patients and studying further under prominent foreign doctors in Siebold’s network. While working in the women's ward at a Western-style hospital, Ine learned alongside men, attending dissections and assisting in operations. Considered a woman of humble birth, her increasing profile and connections led her to a remarkable career frequenting important centers of Western learning in Nagaski, Uwajima, Tokyo, and Okayama. For a time, she was the chief physician of the daimyo of Uwajima and was later invited to serve the Imperial Palace, attending births of the Daimyo and Emperor's family.

Sources:

Williams, Duncan Ryūken, and Ellen Nakamura. “Working the Siebold Network: Kusumoto Ine (1827-1903) and Western Learning in Nineteenth-Century Japan.” Essay. In Hapa Japan: History 1, 1:69–84. Ito Center Editions, an imprint of Kaya Press, 2017.

-

![]()

Olivia Ward Bush-Banks (1869-1944)

“I seemed to have lost my identity regarding the distinctness of race, being of African and Indian descent.”

Olivia Ward Bush-Banks was a literary artist from the New Negro, or Harlem Renaissance era. Working alongside Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and other great writers of the time, she was titled “the grand dame of the literati” throughout society. However, her name is not so commonly shared as the other masters today. Born in Sag Harbor, New York, Banks was predominantly raised by her aunt, who instilled in Olivia an appreciation for both her African and Montaukett Indian traditions that she embraced into adulthood. She was a writer, journalist, and historian, maintaining the tribal record and working to preserve the Montauk language. While working as a single mother of two and caretaker of her aging aunt, she published her first volume, Original Poems. During her second marriage, she mainly lived in Chicago and started the Bush-Banks School of Expression. She was heavily involved in the community as a journalist and spoke alongside NAACP leaders. The Boston Daily Globe reported that she organized approximately “eight hundred colored women” in Roxbury, Massachusetts, to protest against the film The Birth of a Nation, calling the event “one of the largest gatherings of colored women ever assembled in this city.”

Bush-Banks wrote from her own lived experience, which naturally stood outside the current racial purity politics and Black separatist ideologies within the New Negro Movement. She acknowledged how US society compartmentalizes racial identities for political purposes to support the white-settler colonialist regime. Her work pushed boundaries beyond a monolithic African American experience and drew attention to the parallel histories and complex relations between African and Native Americans, calling for collective resistance to white supremacy. Unwilling to follow society’s expectations, she was unapologetically African-Native American.

Her entire literary work is composed of over seventy-five poems, twenty-three plays and sketches, numerous essays and newspaper articles, and a memoir.

Sources:

Hawkes, DeLisa D. 2021. “Olivia Ward Bush-Banks and New Negro Indigeneity.” MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S 45 (3): 104–28.

Young, Kevin. 2020. African American Poetry : 250 Years of Struggle & Song. Library of America: 333. The Library of America.

-

![]()

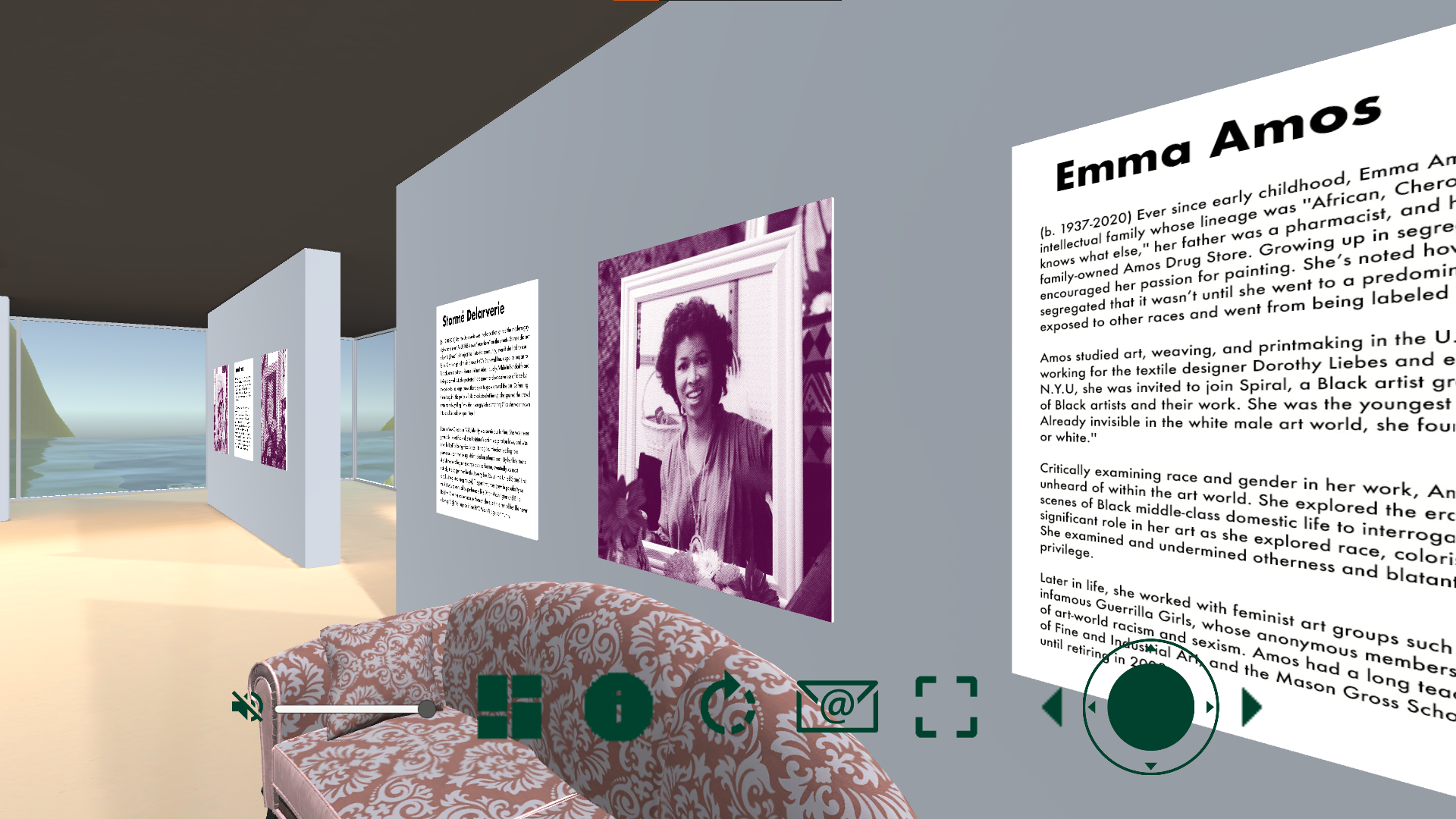

Imao Hirano (1900-1986)

Throughout his life, Imao Hirano was dedicated to helping the Mixed Race community in Japan. In post-WWII Japan, many Mixed Race children had to go through extra steps to become a Japanese citizen — it was difficult to obtain a ninchitodoke, a method that determined citizenship through the father’s bloodline. Labeled as konketsuji mondai or “mixed race problem” in Japan, Imao viewed his involvement in helping them as his calling.

The “mixed race problem” was personal for Imao, he was heavily scrutinized for being Mixed Race: as a boy, he was constantly called an Ainoko (a derogatory term for Mixed Race individuals) by other children; and as an adult, during WWII he was harassed by the government for being a supposed American spy. Imao established a grassroots activist group called the Year 1953 Society to advocate for Mixed Race children. His group helped many Mixed Race children gain access to schools and other privileged spaces, educated the public on Mixed Race issues, and pushed for government cooperation. Imao, himself, even adopted several children. As a writer, he penned a sentimental article, titled “I will be your father: raising the war’s innocent mixed blood children” — a call to all Mixed Race that he was there for them.

-

![]()

Stormé DeLarverie (1920-2014)

“The only time you have to use the past is to stop something...that’s abusing people”

Stormé DeLarverie was the force that ignited the modern gay rights movement. As the LGBTQ2SIA+ community’s own “superhero” on the streets, Stormé did not allow “ugliness” to interject itself into the community; even if she had to use force. On the night of the infamous Stonewall Uprising in NYC, as police began to forcibly arrest patrons, Stormé did not submit quietly. While in handcuffs and being escorted out, she protested harassment and excessive use of force by the police to the large crowd that began to grow around the bar. Defending herself against the police’s futile attacks to shut her up, she spurred the crowd even more by yelling “why don’t you guys do something?” as she was thrown into a police paddywagon. Fuse lit.

Born in New Orleans in 1920, identity was pernicious for her. She was never given a birth certificate due to Louisiana’s anti-miscegenation laws, and was often bullied for being Mixed Race — its tragic culmination leading to a permanent scar after being left impaled on a fence post. By her late teens she left home to begin her career as a performer, eventually, as most notably, the dapper host for the Jewelry Box Revue (the United States’ first racially integrated drag troupe). The performances grew in popularity so much it was celebrated by performers like Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday. After her career as a performer, she spent the rest of her life never allowing “ugly” to happen in her NYC West Village community.

Sources:

Stonewall Veteran’s Wisdom on Ugliness

Klocke, Kirk. 2012. "Stonewall Veteran's Wisdom On 'Ugliness'". Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/41947368.

NY Times’ obit on Storme

Yardley, William. 2014. "Storme Delarverie, Early Leader In The Gay Rights Movement, Dies At 93." New York Times, May 29.

-

![]()

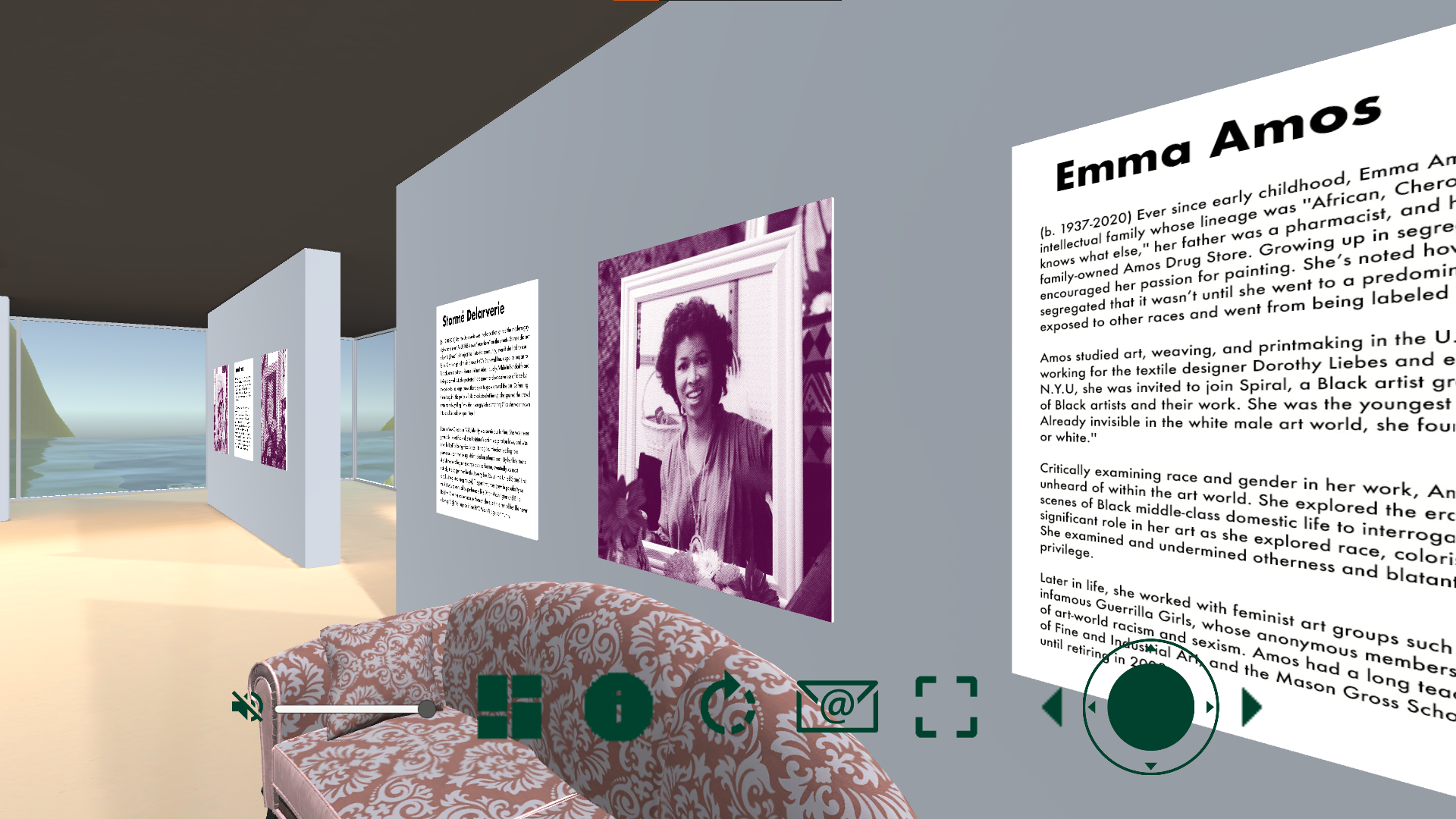

Emma Amos (1937-2020)

''It's always been my contention, that for me, a Black woman artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.''

Ever since early childhood, Emma Amos was an artist. Raised in an intellectual family whose lineage was ''African, Cherokee, Irish, Norwegian and God knows what else,'' her father was a pharmacist, and her mother managed the family-owned Amos Drug Store. Growing up in segregated Atlanta, her family encouraged her passion for painting. She’s noted for saying how the city was so heavily segregated that it wasn’t until she went to a predominantly white college that she was exposed to other races and went from being labeled a child artist to a Black artist.

Amos studied art, weaving, and printmaking in the U.S. and London. In 1964, while working for the textile designer Dorothy Liebes and earning her graduate degree at N.Y.U., she was invited to join Spiral, a Black artist group that discussed the political role of Black artists and their work. She was the youngest member and the only woman. Already invisible in the white male art world, she found that it was ''a man's scene, black or white.''

Critically examining race and gender in her work, Amos explored themes that were unheard of within the art world. She explored the erasure of Black history and depicted scenes of Black middle-class domestic life to interrogate old stereotypes. Color played a significant role in her art as she explored race, colorism, and ambiguity with her figures. She examined and undermined otherness and blatantly criticized white male artist privilege.

Later in life, she worked with feminist art groups such as the Heresies Collective and the infamous Guerrilla Girls, whose anonymous members publically deliver scathing critiques of art-world racism and sexism. Amos had a long teaching career at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art, and the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, until retiring in 2008.

Sources:

Amos, Emma, and Thalia Gouma-Peterson. 1993. Emma Amos : Paintings and Prints, 1982-92 : An Exhibition. College of Wooster Art Museum.

Cotter, Holland. 2020. “Emma Amos, Artist Who Challenged Racism and Sexism, Is Dead at 83.” New York Times, May 30.